ABID AL BOUKHARI, the Black Guard of Morocco: Rise, Power, and Fall of Moulay Ismaïl's Elite Army

A kingdom is a construction, the army is its foundation. If that foundation is weak, the construction falls apart.

In his bold letter to Sultan Moulay Ismail, Cheikh Al Youssi (1631-1691),tried to shake the ruler out of his complacency – and of his mistakes.

Al Youssi, a beloved member of the Alaoui court during the reign of Sultan Moulay Ismail and even during that of Moulay er-Rachid, issued a warning. His letter is as a testament to the kingdom's vulnerabilities of the time.

He wanted to wake him up to the essence of power for any ruling entity : fragile, dependent and precarious without a strong ground to uphold it. He saw the cracks that had been forming beneath the surface of the empire ; an empire caught between internal unrest and external threats. The Alaoui line, though powerful, was not immune to these pressures and had yet to assert their legitimacy, as the 17th century was just seeing the baby steps of their rise. He understood that if the army was not properly fortified, the kingdom’s survival would be in jeopardy.

Al Youssi believed that if Moulay Ismail reformed the military, he could prevent the disastrous fate that awaited the Alaoui dynasty after his death. He saw the impending danger and believed that there was still time to avoid the irreparable.

But why was reform necessary in the first place?

The answer lies with Abid Al Boukhari – the infamous Black Guard. The very force that was initially created to protect and stabilize the empire.

Their allegiance was to the Sultan alone, not to the kingdom or its future. And Al Youssi, understanding that like the biggest part of the royal court, saw them as a ticking time bomb.

Without reform, the Black Guard would be a barrel of gunpowder waiting to explode leaving the empire dangerously exposed after the Sultan’s death.

But Moulay Ismail, entrenched in his own power, would not act and therefore would sealing the fate of the dynasty in a nail coffin himself.

At the beginning of his reign, Moulay Ismail had an unconventional vision for control. A vision that involved a controversial decision: he would not rely on traditional recruits. Instead, he created a force composed of thousands of Black men, women, and children, many of whom were free or even Muslim. These people, who had previously been seen as free citizens, were forced into military service by the sultan, disregarding established Islamic laws which stated that slaves could only be non-Muslim. Moulay Ismaïl’s willingness to break this rule would forever change the course of Moroccan history.

The Birth of the Abid al Boukhari (Black Guard)

When he ascended the throne in 1672, Sultan Moulay Ismail was confronted with a legacy of undermined sultanate control. The throne he inherited from Moulay Rashid (1666-1672) was weakened by internal instability and threats from neighboring European powers particularly the Spanish and Portuguese. The Europeans had advanced in the Mediterranean and on the Atlantic coast. They represented a consistent threat to the central government, distracting it from catering to internal divisions which only further weakened its reach.

The Makhzen (central government = Sultan's administration, based in the capital city of Meknes)'s authority over the vast lands, which extended from the Maghreb deep into the Sahara, was unstable to say the very least. Morocco’s population was split between powerful Amazigh tribes and tribes that claimed Arab descent, groups that held onto their autonomy fiercely and resisted the Makhzen's expansion. The Makhzen struggled to maintain consistent influence over the countryside, which was often controlled by powerful local, Amazigh rulers, religious authorities, and / or foreign invaders (Christians). Tribal confederations such as the Ayt Umalu often saw the sultanate as more of a distant authority than a legitimate ruler over their lands.

Very aware of these pressures from the beginning of his reign, Moulay Ismail, known for his iron-wiled rule and his visionary (some might say original) approach to politics, turned to what he knew most as a solution: reforming the military. However, relying on local Arab and Amazigh (Berber) tribes presented a major risk as tribal loyalties often superseded allegiance to the sultan. These groups would frequently shift their alliances based on regional interests in a socio-political dynamic that would be later known as "Blad Al Makhzen VS Blad as-Siba".

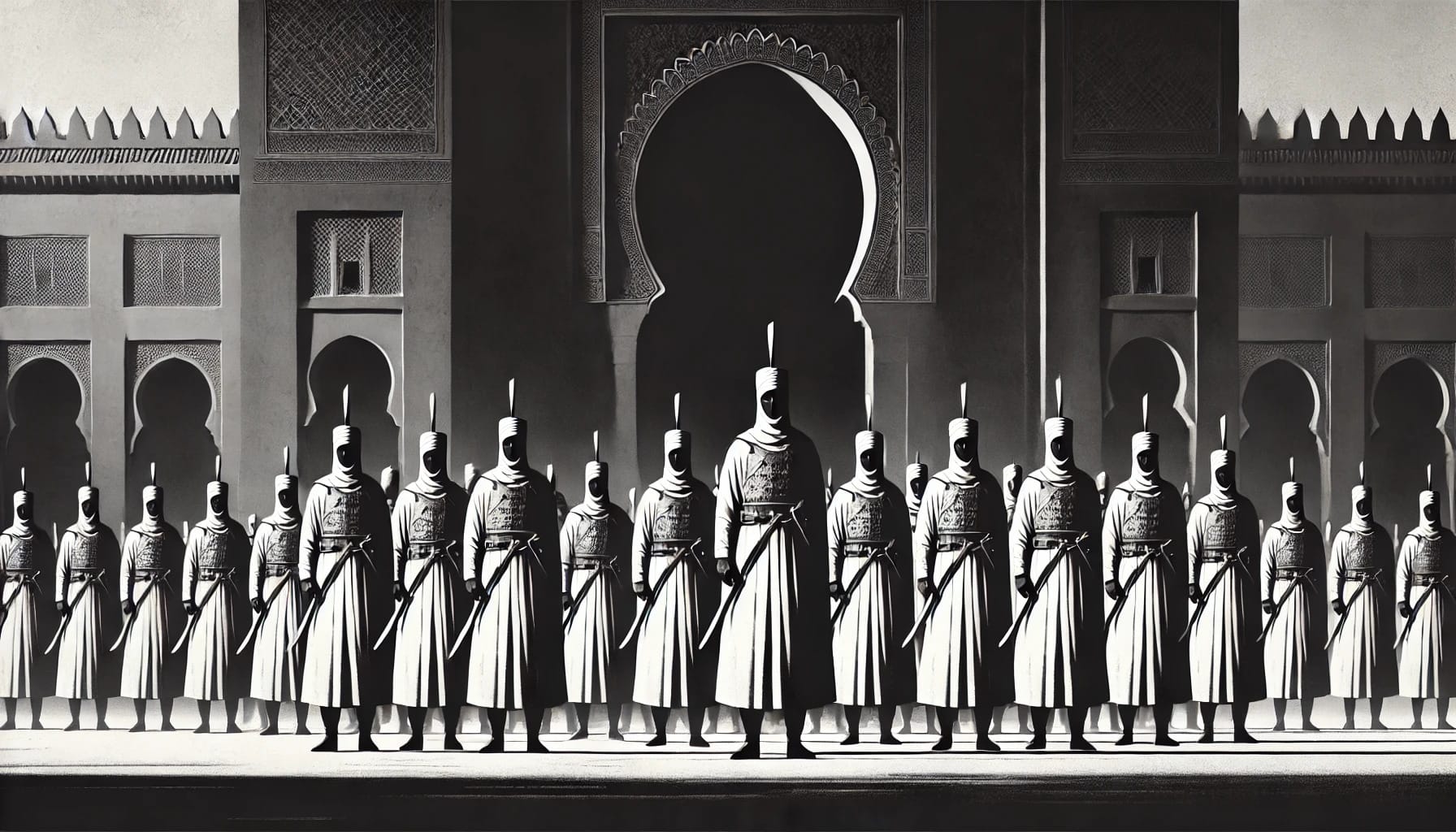

Big problems require big solutions. So, by the mid-1670s, Moulay Ismail began to assemble a massive, unprecedented army, that was only answerable to him ; an army that transformed the history of Moroccan administration for centuries to come : Abid Al Boukhari, also known as the infamous Black Guard.

Unlike traditional Moroccan armies that were based on tribal alliances with soldiers being recruited upon temporary agreements with local leaders that all had their own interest at heart, the Black Guard or Army would be independent, only chained to one interest: that of the Makhzen. A force bound by loyalty not only to Moulay Ismail as a sultan, but also to the divine... Hence their given name, "Abid Al Boukhari" : the Slaves of Al Boukhari.

Because as it turns out, the soldiers of the Black Guard swore an oath on the Sahih al Boukhari, a revered sunni collection of authentic Hadiths (accounts from the Prophet (pbuh)'s life) by Imam Mohammed Al Boukhari (810-870), pledging their loyalty to Moulay Ismail alone. They would obey without question, protect his authority, and enforce his will, often brutally, upon any opposition. Tje binding was both a practical and a spiritual one, tying these men to the Sultan, Commander of the Faithful, through both the sword and the sacred word. In return, he gave them certain freedoms, privileges, and a place in the military structure that no enslaved people in Morocco had held before.

The Black Guardd in Service of the Sultan

The soldiers would be enslaved, then freed and "recruited" from sub-Saharan countries, primarly from Mali, Guinea and Senegal. By recruiting and training Black soldiers, Ismail thought he could effectively sidestep the shifting dynamics of political loyalty and instead create a force whose allegiance was owed directly to him. Enslaving and training individuals without local ties nor tribal affiliations meant that they could be isolated, easily controlled and shaped into an elite entirely devoted to the sultan’s will.

Their training was intense; it built their immense resiliencee. The Black Army was taught to endure hunger, to muscle through hours in armor under the sun, to survive lengthy campaigns – all of that to keep up with Moulay Ismail's grand political ambitions. These men, who had once known little else but laboring agricultural fields or tending to homes as servants, were now learning the art of war. Young recruits would train with older soldiers, isolated from the rest of the population ; battle hardened soldiers passing that "sword memory" down onto new members, forming an echo chamber that intensified their devotion to the Moulay Ismail.

The numbers behind the Abid al-Boukhari, the size of their ranks, were astonishing. At its peak, this force varied between 50,000 and 100,000 soldiers. If we were to combine them with the Oudayas, a separate military corpse under Sultan Moulay Ismail composed of Arab soldiers, that would raise his total strength to nearly 150 000 men : a scale of military power the region had never seen or experienced before.

But loyalty to Moulay Ismail came at a cost. The Black Army, despite their privileges, were still an army derived from enslavement. They were bound to the whims of the sultan, kept under strict control. Their lives were shaped by his commands, and arguably, by his anger. Even as they were called upon to pacify rebellions they were reminded of the limits of their power. They were instruments of Ismail’s rule,, and while they were more privileged than other enslaved individuals in Morocco, their fates were forever tied to the sultan’s satisfaction.

For over fifty years, the Black Army stood as Moulay Ismail's backbone.

Their role was multifaceted. Not only were the Abid Al Boukhari the military arm of the sultan, but they also acted as his enforcers. The Black Guard patrolled the Moroccan countryside collecting taxes, maintaining order, and ensuring that no one defied the sultan’s will. They were feared across the kingdom, not just for their power but for the unique privileges they enjoyed.

A Regional Power, International Reknowned

With each passing year Abid Al Boukhari became more feared, more respected. They were the sultan’s ultimate weapon, made knwon to both local tribes and external powers through the diplomats that were paying Meknes a visit, so much so that it lead them to be mentioned in numerous travel journals.

John Windus, a British diplomat and ambassador to Morocco, was tasked in 1720 with negotiating peace with Sultan Moulay Ismail and local pashas, securing the release of prisoners. His experiences and observations of the Black Army are detailed in his book "A journey to Mequinez (Meknes), which he published in 1725 offering one of the earliest Western perspectives on the immense organisation of Moulay Ismail's force.

A special status

What set the Abid al-Boukhari apart from other military units in Morocco, especially from other slaves, was their status. While most slaves were forced to endure harsh conditions, according to the accounts, Black Guard was treated with a degree of privilege that was unheard of at the time. A French consul appointed in Salé between 1689 and 1701, Jean Baptiste Estelle (1662-1885), even went as far as saying in his memoirs : "This prince established his authority, along with that of his Black soldiers, to such an extent that the Whites (...) became their slaves."

They were paid well, given the right to own property, to expand their estate, and even ranked higher than the white Christian slaves who were present in Morocco. These privileges elevated their position in society, granting them powerr far beyond what one would expect from such an army.

To ensure their absolute loyalty and cohesion, Moulay Ismail isolated them from the rest of Moroccan society. The Black Guard lived in segregated communities completely separate from the general population. They were encouraged – or forced – to marry among themselves, and their children were raised with one purpose—to serve the sultan just as their parents had. This created a self-sustaining system, one where the Black Guard was bound by loyalty not only to the sultan but also to the structure of their own existence.

Longlasting Power & Control

When Sultan Moulay Ismail passed away in 1727, Morocco entered a period of political chaos – yet again. He left behind many (many...) sons. But we'll only focus on the 7 that were each vying for the throne. Without a clear line of succession, the sultanate was thrown into a dangerous uncertainty. A ruler may conquer many lands like Moulay Ismail did, but the real test lies in longevity. And Moulay Ismail had failed to make his intentions clear – if indeed he had any. Now, without him, the Black Army had a choice to make. And with it came an opportunity to redefine their power.

The death of Ismail exposed fractures both within their ranks and within the ruling family. While some soldiers remained loyal to the family line, steadfast in their mission of protecting the sultan’s legacy, others naturally saw an opportunity to assert their power by selecting the new ruler. Abid Al Boukhari, once united by their allegiance to a single man, began to split into factions that supported different claimants to the throne.

In 1728, the Black Army first exercised this power by choosing a leader among Moulay Ismail's sons: sultan Ahmad ad-Dhahbi. Ahmad was, at first, grateful and respectful for their support, but here's where he messed up: he failed to pay their salaries. A classic. Soon enough, the army would turn against him. What followed was a series of coups, counter-coups and depositions, as the Black Army’s factions began to shift their loyalty to different sons of Moulay Ismail.

They were no longer simply soldiers (or were they ever just that?); they were kingmakers, standing in the shadow of the throne deciding on who would be granted the privilege to sit on it. In the years following Moulay Ismail’s death, Morocco saw the rapid rise and fall of several sultans, each brought to power or deposed by Abid Al Boukhari that had gained a sense of autonomy. Once bound solely to the service of a sultan they were now seen as a political force unto themselves.

A great example of that mightiness can be found in (one of the) reign(s) of Sultan Abd al Malik, who had been deposed and reelected multiple times by the Black guard. His was completely at their mercy; they began to assert even more demands, requiruing higher pay, more privileges, and greater respect. When Abd al Malik attempted to curb their influence, withholding their salary and trying to openly favor other groups within the military, the Black Guard deposed him, choosing another of Ismail’s sons, Abdallah, as his replacement in an endless cycle. The sultanate, once an unshakable institution, was now, utterly, subject to the whims of Abid Al Boukhari.

Yet, the army’s role as kingmakers came with a price. Each new sultan viewed them with suspicion, with fear. They grew aware that their loyalty was not absolute. Fearing their power, these rulers attempted to weaken or divide them, as we'll see with Sidi Mohammed often by refusing to pay their salaries or by turning other factions within the kingdom against them. The Black Guard's loyalty became conditional, its ranks restless and dissatisfied with rulers who could not meet their demands. What had once been the most effective law-enforcing weapon in the hands of the sultanate, had become a volatile force : feared and mistrusted by the very rulers they installed.

Betrayal & Decline

The cycle of support and betrayal took its toll on the Black Army. By the mid-18th century, it had become clear that they could no longer be trusted as a unified force. Divided by internal factions, weakened by years of unpaid wages, and fractured by the politics of sultans who viewed them as a threat, the Black Army began to lose its cohesion.

In the 1750s, Sultan Sidi Muhammad (1757-1790) sought to dissolve the Black Army altogether. Determined to break their hold, he divided the army, sending some soldiers to distant garrisons and scattering others across the kingdom. What had once been a concentrated force in Meknes was now fragmented, separated from their brothers-in-arms, and stripped from the influence they once had.

Resentful, disillusioned, many soldiers of the Black Army did resit this forced dispersal by Mohammed III. Their anger broke out into rebellions all across the empire, as soldiers fought against what they saw as an act of betrayal by the very sultanate they had once served so faithfully. But Sidi Mohammed was resolved, remained steadfast in his belief that they had to be stopped; his forces crushed these uprisings with brutal efficiency.

That, was the beginning of the end for Abid al Boukhari.

In a final act of suppression, Sidi Mohammed had issued a decree that allowed local tribes to enslave any soldiers who resisted the order to disperse. A devastating, unprecedented move ; soldiers who had once been part of Morocco’s most elite force were now scattered. Many got captured and enslaved by the same people they had once oppressed. The army that Moulay Ismail had created to ensure loyalty had, through decades of political manipulation and betrayal, been broken, humiliated, torn to pieces across the national territory.

The Last few Breaths, from Might to Memory

The centuries that followed saw the complete collapse of the Black Guard as a military power. By the time Morocco became a French protectorate in the early 20th century, the Abid al-Boukhari had been reduced to little more than a ceremonial unit, a mere shadow of their former strength and glory. From a dominating force that once shaped the course of Moroccan history, they had become a symbolic relic of a bygone era.

What began as a strategic decision by Sultan Moulay Ismaïl to secure his rule ended up creating a distinct community—one that would leave a lasting mark on the history of Morocco, even long after their military might had faded.

Sources Used & Recommended Reads :

Histoire du Maroc, by M. Abitbol

Moulay Ismail et l'armée de métier, by Magali Morsy

The political history of the Black Guard, by Chouki El Hamel