[CONVERSATION]: What Happened to Moroccan History?

As a Moroccan patriot who shares her passion for learning about History, I am chronically aware that I don't know everything nor do I pretend to. Truth be told, I don't think I know much, given the scope of what there is to learn in a single lifetime. And it is precisely because I know this that I feel able to say what I'm about to say.

Since I began sharing my work on Moroccan history through my writing, videos, podcast and social media, I've encountered many responsess that remind me just how easy it is to lose the natural humility one should have when approaching any kind of material, but especially complexe histories. The slope that leads to stepping away from the messiness, and the intricacices of the past, is slippery : in propelling ourselves forward, we often fall into the trap of reducing it to simplistic narratives; forgetting that two things can be – and often are – true at the same time. That A doesn't negate B. That "convenient" doesn't equate to "true". Too frequently, I've seen and engaged with History enthusiasts who look for heroes to praise, or villains to blame, a saga of pure light and shadow, for clarity and closure – and at one point, I've met this attitude within my own self. I believe it's what we call a bias. And while that might sound appealing, and without ever wanting to promote a dangerous sense of relativism, what I'm finding in my learning process is that Moroccan history, especially, rarely offers such simplicity. It defies categorization, doesn't call for neither blind acceptance nor outright rejectionn, but rather a level-headed, almost cold-hearted acknowledgment, as long as it is carefully reported.

So, if you happen to be looking for pro-this, anti-that, neatly packaged conclusions or a desire for certainty, I'm afraid I'll disappoint : you might want to turn to TikTok comment sections, though, I heard they do it best. However if, like me, you like to freely engage with and lean into the gray areas, the layers, the tensions, then my content might be of use to you.

This disclaimer is my invitation for readers, listeners and viewers to engage with Morocco through a nuanced lens. I ask this because how we approach history matters. The way we choose to see, and most importantly share Morocco shapes the way the world understands it entirely.

Let's get into this conversation.

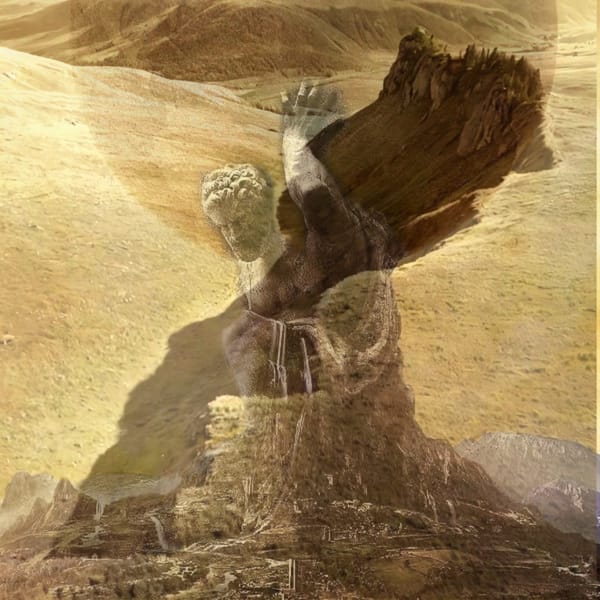

For too long as Moroccans we've been feeling a profound disconnect from our history, which is undoubtely the backbonee of a nation. It is a narrative through which a social body understands itself, the struggles it faces and its place in the larger story of the world. It grounds us, as a nation. It provides us a collective sense of self, which Morocco doesn't chronically lack, I'll give it to you, but could use more of : more self-reference, more wisdom, more of an internal locus of control, more national coherence, stronger roots that sink deeper into the land. The ability to recognize and celebrate the shoulders we stand on : to trace the invisible line between who we were, who we are, who we could be and all in all, who we ought to be.

Just an individual without memory can't possibly form a stable identity, so too a society without a sense of its own past, without a soil beneath our feet, cannot find stillness in its posture, and survive the winds of time. But luckily, "by force of things" and despite the general disconnect, the limited access to resources and geographic scattering of Moroccans across the globe, if you visit Morocco it shouldn't take you too long before realizing people have held on to a solid thread that binds us to the past and to each other. Memory has been saved by oral storytelling, shared traditions that span entire cities from Tetouan to Lagouira, daily habits, lifestyle patterns. Even the language holds within it chapters of the book, with influences ranging from Tamazight dialects to Arabic to Spanish and French.

As Moroccans, I found we often get a sense that our own story is something obscure, fragmented, and less accessible than the narratives of nations across Europe or even neighboring countries; and though unfortunate, that impression is valid. In Europe, history is displayed in monuments, celebrated in school curricula,, meticulously preserved in public museums / archives, that are made relatively accessible to just about anyone. The European "yesterday" is laid bare, sometimes romanticized, and presented with a continuity that has the potential to instill identity from a young age – though in practice, it doesn't always.

In Morocco, however, our relationship with history has long been tainted by gaps in collective memory ; our historical awareness, a patchwork. Pieces of folklore, stories passed down orally, and fragments in school textbooks that barely ever scratch the surface, carefully curated or simply ignored. And the reasons, are many.

Post-independence, priorities often focused more on modernization than on historical preservation, and understandbly so. The delayed pace of development exacerbated by the protectorates (which also set Morocco on the path to modernization, a paradox that cannot be ignored and that separates Morocco from other colonies) meant that Morocco was often playing catch-up. Struggling to build, on the one hand, upon what had been initiated by colonial policies, and rebuild, on the other hand, what had been broken by decades of occupation, all while trying to establish its own systems of: governance, knowledge, and international support. Urgency creates hurry which creates competing priorities, which creates missteps, mistakes, taking the form of poorly executed reforms, sometimes the replication of ineffective colonial models like balls and chains, but most importantly, the centralization of power around the monarchy that helped the country naviguate new challenges. This also meant the sidelining of local leaders and traditional forms of governance that had existed in the country for centuries, leading to a top-down approach to governance which extended to education as well, if not first thing. The Arab-islamic influence became the dominant narrative, and for the teaching of Moroccan history in schools this meant a narrative that downplayed or even omitted the complex dynamics of power, of influence, that existed in the region way before colonalism and during the fight for independence, bleeding on the first few years of modern Morocco. History education became more about reinforcing the legitimacy of the government (a legitimacy, though deeply respected and unquestionable today, that was certainly not a given before the occupation) rather than a more nuanced understanding of it by Moroccans. After the occupation, the narrative was simplified : on paper, this strategy was meant to promote unity, but what it did was try to prevent conversation. Had Moroccans been taught a broader view of history, one that encompassed the conflicts, the regionalism, the particularismm, one that would've sparked more critical engagement with history, it might've led to a national energy that the government did not want to have to deal with on top of its other competing priorities, which we've mentioned previously.

By narrowing the historical narraitve like it did, the central government of the time meant to keep the national discourse aligned, "the country together", which one may see as a protecting shield custom-made for Moroccan society in a rapidly-changing world that required territorial cohesion, while others will rightfully regret the marginalization it caused, as it left little to no room for a truly inclusive historical conversation that could have encouraged a different vision of Moroccan history, and therefore identity.

While the state focused its attention on post-occupation damage control and development, it felt like it had to do so while maintaining the historical and religious power structures that gave the Sultan, then the King, both authority and legitimacy. What appears, bright and clear, is a tension between building a modern centralized state that mirrored to the T some colonial models of governance (NB: if you're interested in this topic, I highly recommend you conduct further research on the movement of post-colonial "constitutionalism"), and choosing unilaterally what social and cultural foundations to maintain. The stakes were high and so was the rush, leading to policies that, at times, turned out to be more reactive than reflective of the deeper needs of Moroccans.

Many Moroccans maintain that the top-down approach the monarchy used to secure Moroccos place in the post colonial world, served as a stabilizing force in a period of rapid change, while others, on the receiving end of that approach, highlight the limited the depth of meaningful political reform.

In our pursuit for self-determination, post-independence Morocco had to shake many hands from different "camps" on the geopolitical scene. It had to contend with external influences both from former colonial powers and global "superpowers". It had to see right through a sea of sharks and oxygen, sort through every foreign agenda, competing interests, and carve out a place for itself ensuring its sovereignty. That said, and while we could've hardly avoided these circumstances given the weight of colonial, global and also national political dynamics,

All this talk about post-independence Morocco aside, it's time we approach the subject from the angle of colonialism. In fact, as much as it contributed immensely to uncovering it through extensive research, putting the pieces of its scattered puzzle back together and keeping track of it, decades of occupation have also undoubtely rewrote and marginalized the History of Morocco, to serve agendas. It has fractured the narrative. When Morocco was carved up by colonial interests, so too was our understanding of who we were; history was rewritten or suppressed, figures of resistance portrayed as rebels. Today, archives are scattered, tucked away in private collections, university archives or state-protected vaults guarded by bureaucratic walls that make them inaccessible to the very people who most need them. Access to these archives, when it’s granted, is costly. The language of colonial documentation is yet another barrier : records are often in French or Spanish as these languages are tied to the powers that once sought to sink their administrative claws into Moroccan soil.

And beyond the grip of colonalism, there’s also the weight of internal politics. Highly sensitive periods in our history kept in the dark to maintain social harmony or to avoid re-igniting old wounds, or to preserve the integrity of bilateral relations (with France, for instance).

As a result, the last few generations of Moroccans (myself included) have been indirectly instructed to look outward for inspiration and study “world history” while their own history remains un/underexplored. This disconnect isn’t just academic, if only it was ! It is emotional. It creates an identity gap, that leaves us feeling like Moroccan history is just out of reach, tainted with missing links & shadowed by silence. And, undoubtely, the part of the Moroccan body that feels it especially is the Moroccan diaspora.

Through my experience as an international student, I found that for Moroccans who had spent their entire lives abroad, this connection to history becomes even more urgent. The Moroccan diaspora is vast, it is powerful – it is an asset for the country's development. But it is often wrestling with the sense of who they are and most importantly, where they fit ; a kind of duality, of always being both Moroccan and something else : Moroccan-Spanish, Moroccan-French, Moroccan-British. As empowering as it may be and often is, especially in terms of living conditions, it often also complicates identity as psychological studies show (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2840244/) creating a longing to feel that sense of belonging without condition. The further away you are,, the stronger the pull to know where you come from.

The diaspora faces the same barriers as the "locally-grown" Moroccan youth : a history that is, if ever existent, reduced to distant clichés, echoes, half-truths. Life in societies that see Morocco as simply a place of beautiful landscapes, a touristic hub, an “exotic” escape, makes it easy to feel disconnected. In those circumstances I tend to find that the efforts to reconnect should be made from the expatriate side. That being said, it is also the state's responsibility to ensure that that umbilical chord remains strong. For Moroccans living abroad, picking up on these truths can be an anchor that brings them back to "where they came from", as they might often get told, not as a place to escape from but as one to contribue to. It offers a connection that doesn’t require explanation or justification : it simply must exist, transcending borders and languages.

For generations, the ordinary Moroccan’s understanding of their past has been handed down as folklore, oral histories, experience, that are though are rich remain incomplete. Gaping silences are left where documentation could provide nuancee, insight and empowerment. Without an active effort to revitalize our historical archives and make them available, a collective determination to reclaim these narratives as our own, we risk remaining forever reliant on secondhand interpretations, external observations. Promoting Moroccan history requires a shift that is as grand as it is bold.

My name is Ayah, and I hope to achieve all these things with you.

I am 21 year-old Moroccan student of law and philosophy with a fire for knowledge that just. Won’t. Die. As you've probably gathered by now, history the way I see it isn’t something to be tediously memorized, but rather felt, lived and passed onto others. Yet I know how rare that feeling is for so many of us, because for years, I too was stuck on the outside, pathologically curious but blocked, wanting to understand the full scope of what it means to be Moroccan but hitting as many walls as I had questions. I could've dug deeper, and that is exactly what I did, because as it turns out, have always been quite the reader... to a fault, sometimes. But you shouldn't have to browse through as many resources, and it's my committment to make sure you have access, through my storytelling, to Morocco’s story, as it is surely out there: buried in French, Arabic, Spanish and English textbooks, waiting to be noticed, confronted, and pieced together.

What I hope you pick up on from my work is that History is a weapon against erasure and a shield against misrepresentation.

I hope you enjoy the ride.