[DOSSIER]: The "Moroccanness" of the Sahara, a History of Sovereignty and Conflict

When it comes to the Moroccan Sahara, one thing has always been true : it speaks to those who are willing to listen.

Last week, we commemmorated the 49th anniversary of the Green March, the event in which King Hassan II famously declared : “This march made of us a new people. A new Morocco has just been born.”

On November 6th, 1975, the Green March unfolded as a living, breathing expression of purpose, unity, and self-reference. Tens of thousands of Moroccans, 350 000 to be precise, gathered on the southern border. The crowd surged forwardd, like a growing wave ; a self-fulfilling prophecy of unarmed men women and even children with only 3 symbols in their hands that mirrored exactly the Moroccan slogan : copies of the Quran (”Allah…”), the national flag (”the country…”), and portraits of Hassan II (”…the King.”) Their numbers were expanding with each city they passed by, from North to South, binded by the rythm of their footsteps, the growls of their cars, and the drums of their hearts.

Recently, in a turning point for Moroccan diplomacy King Mohammed IV hosted French president Emmanuel Macron and a delegation of top officials in the capital of Rabat; a high-level meeting, with stakes just as high, that marked a landmark moment for bilateral relations between Morocco and France, as France had just formally recognized the Moroccan sovereignty over the Sahara region. An affirmation Morocco has long pursued on the international stage, and effectively, a diplomatic victory that reflects decades of strategic engagement by the Kingdom, carefully cultivating and nurturing partnerships, leveraging its influence to build an international consensus around the Moroccan identity of the Sahara desert.

Far from being just yet another statement of intent like we’ve been getting used to, this represents a true shift in France’s approach within the centuries-old diplomatic dialogue with Morocco. It showed an evolution, from decades of cautious silence and neutrality to a stance of open and resolute support; to an alignment on a vital issue for Morocco. For Morocco, this meant finally seeing the fruit of years of strategic and patient diplomacy; a diplomatic project, to outward completion.

Yet this meeting is just one chapter in a much longer story of Moroccan diplomacy with the Sahara at its very core. Since independence, the Moroccan government has made it very clear that the Sahara is as essential to Morocco as a limb to the body. When the European protectorates came to an end in 1956, the Sahara remained largely under foreign control which left the nation with a wound, a sense of dismemberment. Despite the Kingdom’s consistent efforts to reclaim the land as its own, the early years of independence presented a very harsh reality for the country to face. After the departure of the Spanish, the pressure of a post colonial world, paired with the diplomatic currents of the Cold War era as well as the delicate balancing act of newly formed alliances all left Morocco fighting an uphill battle that also involved a struggle against the weight of an international system, which would at times ignore local histories in favor of political expediency.

The government’s committment to the affirming of Moroccan sovereignty over the region truly shaped its diplomatic approach.

However, in this article and as much as exploring the historical evidence affirming Morocco’s sovereignty over the Sahara is critical to understanding the depth of that claim that is too often disregarded, it would demand an entire series of articles. Here, I’ll set it aside to focus on the origins of the conflict itself: how an issue once as clear as Morocco’s own borders, transformed into a point of international tension.

Sources will be listed at the end of the article.

From the earliest of days Moroccan sovereignty has been a recurring theme in the story of the Sahara. It cannot possibly be reduced to a mere tale of borders, deprived from any substance: it is a matter of reviving a deep, ancestral, historic, essential connection between the Moroccan state and the tribes of the Sahara.

The 19th century was a time of extensive territorial conquest by European empires, who raided through Africa to assert their domination over the continent. In 1884 was held the Berlin Conference, where European countries divided it amongst themselves like you would a piece of cake, disregarding the established societies, cultural ties and the borders that existed long before their arrival; and Morocco, despite its ancient dynastic history, fell victim to this partitioning, due to the central governmnent’s weakening since the beginning of the century, the state’s debts, internal strife, and other reasons which we’ll get into into upcoming articles. Though the country’s sovereignty was not entirely eroded, vast territories including the Sahara region were stripped away and cut into pieces, divided into protectorates managed by both France and Spain.

The southern territories of the Sahara that were part of Morocco's historical lands were among the areas that fell under Spanish control. Spain's claim over the desert was based on the colonial idea that the region was, upon its troops’ arrival, a terra nullius, a legal notion that refers to "a land that belongs to no one”. A claim that ignored not only the long-proven ability of Saharan tribes to effectively govern themselves, but also and most notably the back and forth allgiance of a large number of them to Moroccan sultans, to the Makhzen, who administrated the region, through the centuries-old tradition of the “bey’a”. This colonial oversight created fractures in North Africa and planted seeds of conflict that would end up resurfacing long after the colonial empires dissolved...

On June, 27 1900, the Treaty of Paris was signed between the kingdom of Spain, and IIIrd French Republic, where both powers agreed to limit their influence to the northern boundary of Sahara, what is known today as “Cap Boujdour”.

Colonial domination ignited a fierce resistance in Morocc throughout the desert. In the Sahara, a figure emerged in the fight against colonial rule: Cheikh Maa el-Aynine, known as the "Blue Sultan”; an educated and spiritual leader who became a symbol of defiance, rallying local tribes, inspired by his loyalty to Moroccan sultans and leading numerous battles against both the Spanish and French forces. Even after his death, his legacy was carried on by his descendants.

Morocco's push for full independence intensified following World War II, as colonial powers weakened as a result of the destruction it caused. Through a combination of negotiation and a good dose of handshakes, Morocco reclaimed many of its territories including 2 enclaves of immense importance : Tarfaya in the region Laayoune-Saqia Al Hamra in 1958, and later Sidi Ifni in 1969.

But Hassan II, at first, chose not to push Spain too hard over the issue, as it would mean ruining the entire process. As a way to thank Francisco Franco for this diplomatic gesture and most of all, to encourage Spain to grant self-determination to the inhabitants of the Sahara, king Hassan II completely dropped its ministry with Mauritania and the region. And it worked. Spain started leaning more and more into a decolonization process but still kept control over its mining resources, exploiting them freely.

The question of the “Moroccanness” of the Sahara moved to the international stage in the 1960ss or so, a decade befrore the Polisario Party was ever even created, and was met with the involvment of the United Nations who issued the Resolution n°A/5514 in which it classified the region as a “non-autonomous territory” as it was occupied by Spain. Morocco was seeking the end of these remaining colonial ties over the region.

Things changed in 1974, when Franco said that Spain would recognize fully “the Sahraoui people’s right to decide their future”, which did not reflect a genuine committment to the self-determination of the people in the region. The very notion of the “Sahraoui people’s right to decide” was problematic for several reasons, when applied to the Sahara.

First, the term Sahraoui was poorly defined in the context of the region. While Franco’s statement suggested a distinct, homogenous group, the reality was more complex and thus, more difficult to grasp for a colonial structure that held and had little interest in the History of the region. The people of the Sahara are a diverse web, chain, of tribal groups from various backgrounds ranging from Amazigh (mostly) to some even Arab-descending, but that all shared economic and political ties with the Moroccan state on different levels. Franco in his statement also suggested keeping a puppet government, the “Sahraoui jamaa”, to maintain Spanish influence.

King Hassan II’s response was swift. In 1974, the Moroccan government with Spain’s support, asked the UN to send a mission to the Sahara, and by 1975, he had sent an appeal to the ICJ (International court of Justice) exhibiting historical evidence that Moroccan sultans had long had an authority on the Sahara. While the court acknowledged these ties of allegiance (” information and evidence presented to the Court indicate that, at the time of Spanish colonization, there were legal ties of allegiance between the Sultan of Morocco and certain tribes living in the territory of Western Sahara”), the international judge didn’t grant Morocco the unchallenged sovereignty it was demanding. In an advisory opinion issued on October 16th 1975, the ICJ, upon analyzing the evidence, came to the conclusions that the territory the Spanish invaded, Rio de Oro and Saqia al Hamra, “was not a land without an owner (terra nullius) at the time of colonization by Spain”.

It was only then, after receiving a clear affirmation from the ICJ which made the historical ties of Morocco to the Sahara known to the international community, Hassan II pressed “play” on his ambitious plan. Despite the setback the half-conclusions of the ICJ represented, the king remained unphased ready as if he had foreseen the moment. He orchestrated a historic event to fully materialize and desplay the weight and resonance to Morocco’s claim.

In November, 6, 1975, the Green March saw 350,000 Moroccan civilians march unarmed into the occupied Sahara. This act of peaceful and most importantly collective will, sent a powerful message to the international community, to Spain and to the world.

On November 9, King Hassan II paid a visit to the Spanish minister Carro Martinez. Their discussion must have been conclusive, given that on the same day, the King declared the Green March completed and ordered all the volunteers to retreat after they had reached near the border of the disputed territory.

The Spanish were already weakened by internal political strife following the death of the dictator Francisco Franco; so, it agreed to transfer all administrative control of the territory to both Morocco and Mauritania, a withdrawal of power scealed in the terms consigned within the Madrid Accords (November, 14, 1975), and materialized by the Spanish’s departure from Villa Cisneros on January 15, 1976.

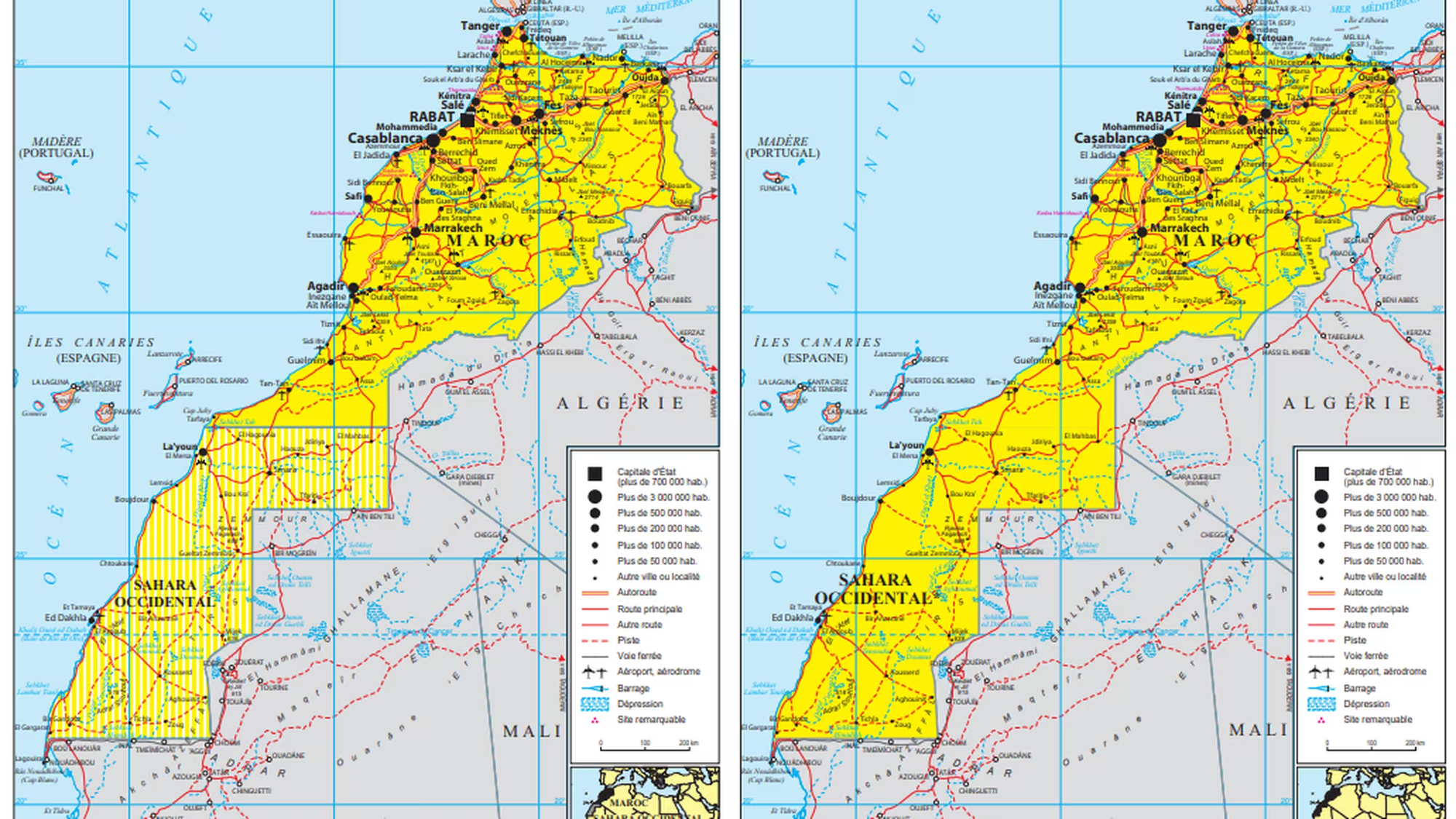

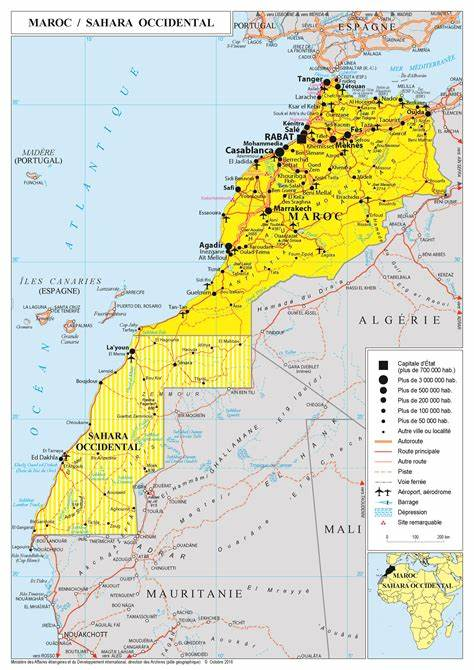

Morocco took back control of the northern 2/3 of the Sahara while Mauritania took the last souhtern 1/3 portion. However, later on, in 1979, Mauritania withdrew its section and Morocco asserted back control over the entire territory.

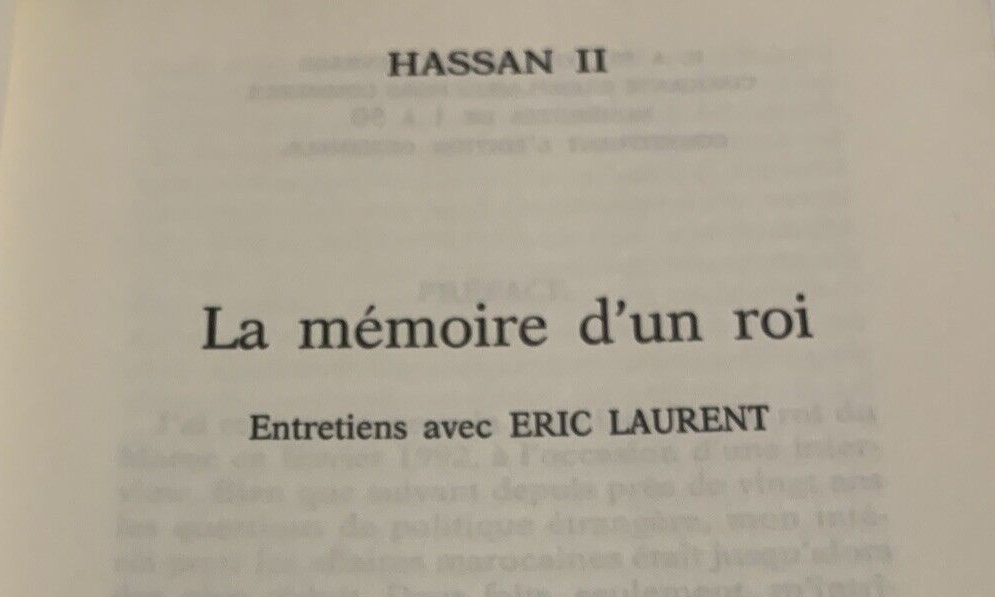

In his memoirs (La mémoire d’un roi, by Eric Laurent, page 184), when journalist Eric Laurent asked him how he responded to those who labeled him an absolute monarch, King Hassan II drew the following parallel : he compares the effects that the Green March had on his rule and authority, to that of World War II on General de Gaulle and to that of Sultan Mohammed V’s exile in 1953. It asserted it; sat it in stone, endorsed him with legitimacy.

The entire Moroccan political spectrum was engaged in the conversation. The members of the Istiqlal party, which had fought for Morocco’s independence, were sent away as envoys to defend Morocco’s cause in the Middle East, in Europe as well as in Gulf countries, figures like Allal Al Fassi who passed away during his leave as he was discussing the issue with the Romanian president. This is also when the Moroccan Jewish community started playing a role in lobbying American leaders and Congressmen to support Morocco’s reclaim of sovereignty over the Sahara, an effort that was encouraged by King Hassan II. However, not all Moroccan parties endorsed that claim: the left-wing Ila Al Amam movement led by Ibrahim Serfaty advocated openly for “Sahraoui determination”, which resulted in them being arrested in 1974 and sentenced to life in prison in inhumane conditions.

But not even a month after the Spanish had left, in February 1976, Morocco has faced opposition from the Polisario Front: a Sahraoui nationalist movement that had been created in 1973, was groomed and is supported by Algeria. From there, the conflict escalates. That is precisely when Mauritania withdrew from its section of the Sahara as we mentioned, after suffering casualties from the attacks of the Polisario to Morocco and agreeing to align with the Polisario.

Despite Morocco consistently emphasizing that the Sahara is historically, culturally and politically Moroccan, coming in guns ablazed with strategy and evidence, the Polisario sought to establish an independent Sahraoui Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). While Morocco had made diplomatic progress, the road ahead was long and far from simple, because as the Cold War divided the world, it was now Algeria backed by its socialist allies including Libya and the Soviet Union, who strongly supported the creation of an independent Sahraoui state. This support, rooted in Algeria’s strategic considerations, in a desire to maintain its status as a major regional power in the face of Morocco’s growing diplomatic alliances with the MIDmaterialized through the Polisario Front, a nationalist group formed in 1973 advocating for Sahrawi independence. This proxy conflict, set against Cold War rivalries, led to armed clashes between Moroccan forces and Polisario fighters, intensifying a struggle that would last for decades.

The “war” continued and by the early 1980s, Morocco had built a line of defensive “sand” wall along certain territories in the Sahara, known as the Berm, across the desert. Meanwhile the Polisario focused on smaller and localized attacks, still backed by Algeria.

In 1981 however Hassan II surprised many: at an OAU summit, he suggested, out of the blue, a referendum in the disputed Sahara territories.

However, it must be known that since 1975, over 65 UN Security Council resolutions paired with more than 120 reports by the UN Secrety general, have never labeled once Morocco as an “occupying power”, nor did it classify the Sahara as a “colony” ; and this is not due to a lack of authority, but simply because the Organizatio is well aware that no grounds exist for such designations. International law and specifically the 1907 Hague Regulations as well as the Geneva Convention defines an “occupying power” as a state that is controlling another, sovereign one, during an armed conflict. Morocco’s reintegration of the Sahara in 1975 did not meet any of these criterias.

Within Morocco itself, there were also diverging approaches, though burried by the administration. Some officials, such as the Minister of the Interior Driss Basri, advocated for a military approach (which, the least we could say is that it was very "on brand"...) while others believed that diplomatic and legal solutions should and would ultimately lead to better results.

By the 1990s, the Cold War was ending, which meant that the political landscape of the world was also shifting. The UN sponsored a series of negotiations, tried to come upon a peaceful resolution to the conflict leading to talks of a referendum on self-determination. While these ideas gained a certain momentum and where positively endorsed by the Moroccan government as a means to a better decentralization of the territory, as it turns out, disputes over over matters of eligibility completely derailed the progress.

In a logic of decentralization, in 2001, Morocco has demonstrated its willingness to support a framework agreement for its Sahara region. This framework supports the idea of devolved powers to local structures that would allow for a more effective administration of this region. It is thought-out, meant and designed to improve governance in a region that is geographically quite distant from Morocco’s main urban centers, for better local management. It should not be interpreted as a change of heart, an acknowedgment of any change in the region’s status whatsoever, nor should it be seen as a step toward separation.

In 2003, the UN Secretary general referred to Morocco as “the administrative power in the Sahara”.

Morocco kept looking for a feasible solution that didn’t violate the integrity of its claims while allowing for some flexibility. In 2007, it proposed a plan for "enhanced autonomy" under Moroccan sovereignty which offered the Moroccans of the Sahara a Western Sahara residents a significant degree of local governance while maintaining Morocco’s territorial integrity. Despite the reject of the plan by the Polisario, King Mohammed VI took Morocco’s diplomatic efforts further and went as far as advocating for it at the United Nations..

Morocco’s autonomy proposal gradually gained international support. Several African, European, and American nations viewed it as a realistic, viable solution to a conflict that had resisted resolution for decades. The turning point came in 2020 when the United States formally recognized Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara as part of the Abraham Accords, a significant diplomatic breakthrough for Morocco. Furthermore, a growing number of African and Arab countries have since opened consulates in Laayoune and Dakhla, signaling their support for Morocco’s claims.

Over the years, many a country has either withdrawn or completely frozen its recognition of the Polisario Front: 51 countries in 2019.

Spain which has long been connected to the issue, if not at the very initial core of it as we saw previously, also shifted its stance. In recent years, Spanish leaders have officially endorsed Morocco’s autonomy proposal as the "most serious, realistic, and credible" solution, which adds signficant diplomatic weight to Morocco’s reclaim of the region.

Morocco’s proposal for autonomy is based on the idea, the belief, that Moroccans living in the Sahara, who are fully integrated into Morocco’s administration, should have more local control, with local governance structures that include local parliamentarians, and full-on plans of “désenclavement” to improve the area and ensure sustainable developemnt being conducted.

Before 1975 the Sahara was quite isolated due to economic and most importantly, the political unrest. But once Morocco took control “in practice” it invested heavily to open up the region. These efforts have included majorr investments in areas like phosphate exploitation (Bou Craa+), with the goal of fully integrating the Sahara into the national economy.

SOURCES :

https://cinqcontinents.geo.unibuc.ro/2/2_1_Chmourk.pdf

“Histoire du Maroc”, by Michel Abitbol

“La mémoire d’un roi”, by Eric Laurent

“Marocanité du Sahara”, by Mustapha El Khalfi